Parliament of Canada

The Constitution of Canada is not an instrument for the Government to restrain people, it is an instrument for the People to restrain government.

In a country, Law typically and exhaustively covers the complete system of law. The Constitution of Canada for example, a common law country with legislative practices in the English tradition of a Parliament, can modify the existing common law only to the extent of its express or implicit provision, but otherwise leaves the common law intact.

A code or act, which must find its source in Law, is developed, and used for simplicity. It replaces the common law in a particular area, leaving the common law inoperative unless and until the code is repealed.

Legislative Assembly of British Columbia

Unravel the complexities of provincial governing policies, processes, and procedures.

How decisions are made, how policies are implemented, and how laws are enacted.

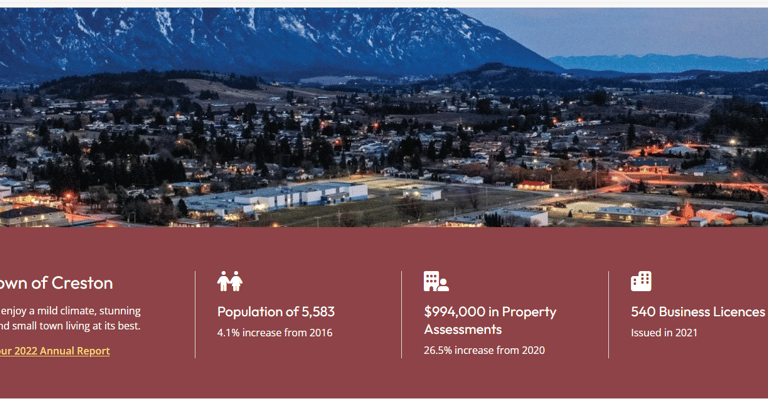

Town of Creston

The Purpose of Civil Municipal Government is to 'ensure' local values and local control. Discover the importance of the Mayor and Council being a transparent governing body and Town Hall's Chief Administration Officer (CAO) and Department Managers (DMs) being accountable to the Public Trust.

Public Legal Education

Mission Statement

To promote peace and prosperity through public understanding of the Rule of Law and the principles and practices of Due Process.

Empowering the People with the knowledge to protect their rights and promote good governance.

Government of the People, by the People, for the People.

Canadian Center For Self Governance

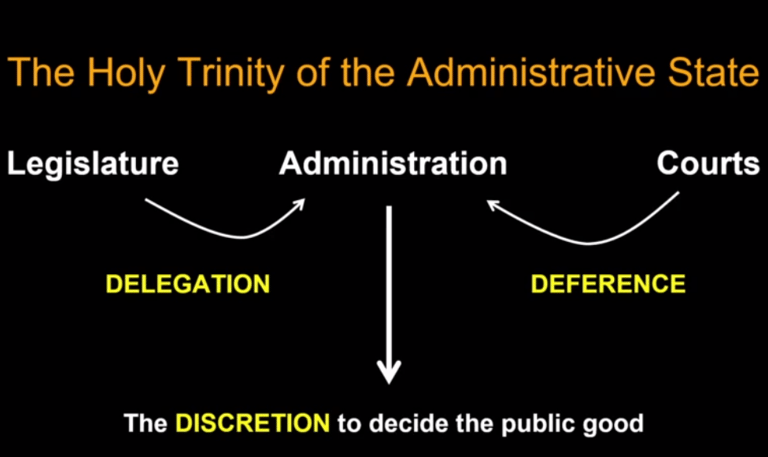

Administrative Law

No administrative court supersedes the Constitution.

No administrative law can bind a citizen or a person.

No administrative tribunal can be referred to as a court.

No administrative adjudicator can be referred to as a judge.

No administrative process or tribunal can describe its processes in terms such as order, subpoena, warrant, or the record, as these are reserved for constitutional judiciary.

Legal Order

Public Law

Statutory

Regulatory

Administrative

Criminal

The Bill of Rights 1960

Access to government departments

Duty of care and obligation to do what is right

Private Law

Tort - Civil and Common - Intentional Negligence

Contract - A meeting of the minds

Governs actions and activities of individuals

Implied and explicit consent

Duty of care

Judicial Review

All legislation is judiciable

Constitutions

The Constitution of Canada 1867

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms 1982

No Administrative Law Can Bind a Citizen or a Person.

This is a strong assertion and touches on a deep tension in Canadian governance between constitutional supremacy and the reach of administrative law.

Legal Theory and Advocacy

Citizen vs. Person in Canadian Law

Citizen: In constitutional and civic terms, a citizen is someone who holds political membership in the state, with rights and duties under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Person: In legal terms, “person” is broader. It includes citizens, permanent residents, corporations, and sometimes even entities recognized by statute. The law often uses “person” to ensure coverage beyond just citizens.

Administrative Law’s Reach

Administrative law applies to persons because statutes delegate authority to regulate conduct broadly (e.g., licensing, zoning, taxation).

A citizen is protected by constitutional supremacy, meaning no administrative decision can override Charter rights.

A “person” (such as a corporation) may be bound by administrative law in ways that don’t directly implicate Charter rights but still fall under statutory delegation.

Constitutional Supremacy

In Canada, the Constitution Act, 1867 and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982) are the supreme law.

Any statute, regulation, or administrative action inconsistent with the Constitution can be struck down by the courts.

This means administrative law cannot override constitutional rights of citizens and are ultimately bound only by laws that pass constitutional muster.

Administrative Law in Practice

Administrative law governs the actions of agencies, boards, and tribunals.

These bodies do not have inherent authority; their powers come from enabling legislation.

Tribunals can issue decisions, orders, or penalties, but those are always subject to judicial review in superior courts.

Importantly, administrative tribunals are not “courts” in the constitutional sense, and their adjudicators are not “judges.” They operate within delegated authority.

Where the Claim Holds True

No administrative tribunal can bind a citizen in a way that contradicts constitutional rights.

Administrative processes cannot create obligations beyond what Parliament or provincial legislatures have lawfully delegated.